|

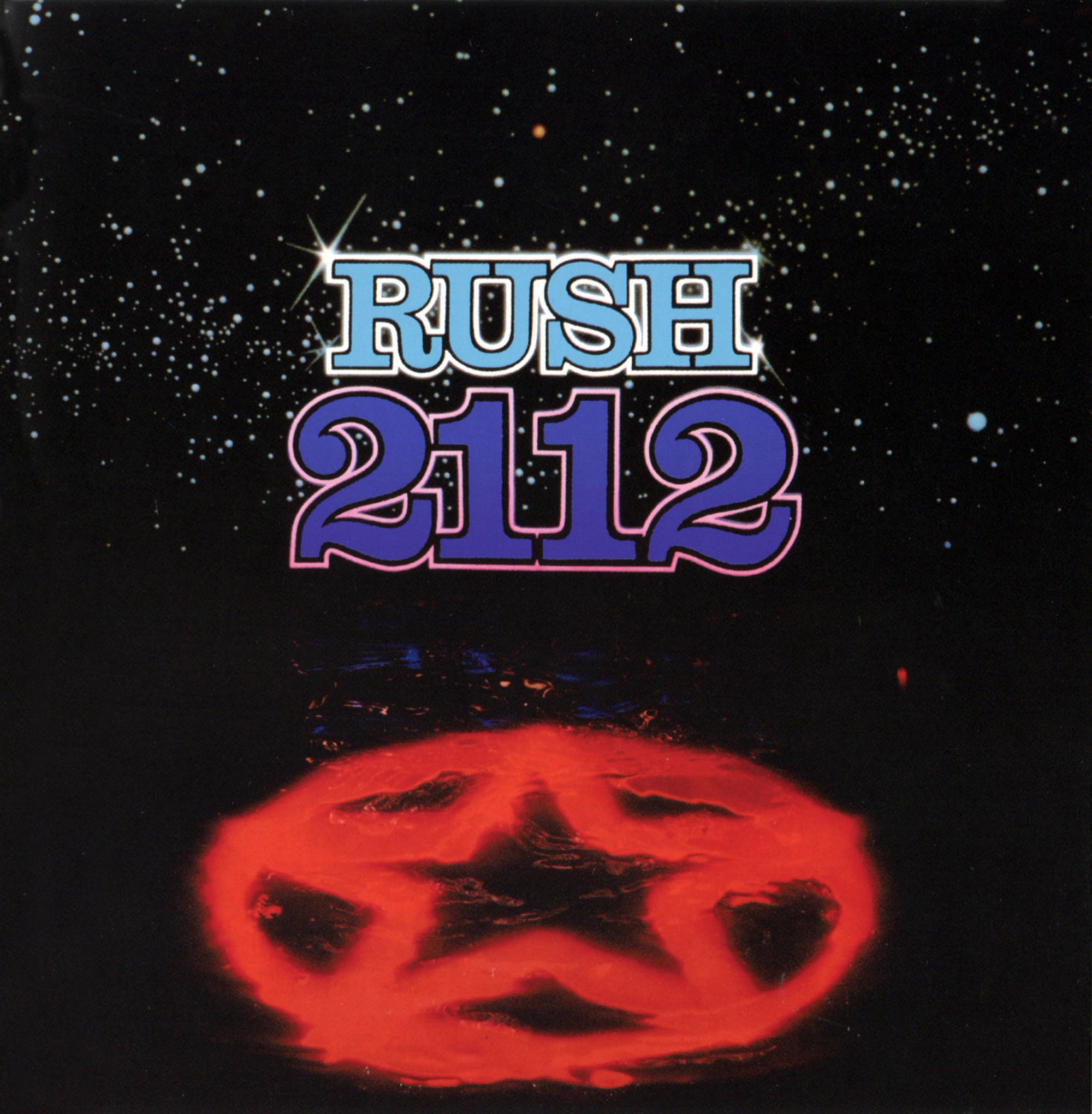

| The cover of Rush's 1976 album 2112 |

So, during my long commute to work today, I had a thought. The thought was brought about by the fact that for the last two days, I’ve been listening to Rush’s 2112, A Farewell to Kings, and Hemispheres all in sequence on my ipod (It was free! I won it! I can’t just not use it! proceeds went to AIDS!).

Anywho, the thought was this: why hasn’t anyone tried to jump on the “let’s write a poorly scripted musical based on popular music by a band that everyone loves” bandwagon using the music of multi-platinum Canadian prog-rock power-trio Rush?

Well, I saw “We will Rock You,” the poorly scripted musical based on popular music by Queen about a year ago and was struck by how easily a musical can become a hit by coming up with a pointless plot in order to loosely string together popular songs.

I am inspired by the fact that Rush’s epic songs actually have a plot of their own, courtesy of Neil Pert’s lyrics. I realized that it wouldn’t be too hard to connect the 20 minute “2112″ with the approximately 30 minute “Cyngus X-1″ duology. that’s almost an hour of music right there. Throw in some dialogue, and a couple of other songs and you’ve got yourself a decent musical. So, here, for your pretend-enjoyment, is a mock-up plot synopsis of a hypothetical “2112: the Musical.”

Act I:

The not-so-distant future: Man is on the technological verge of intergalactic space-travel, but no life outside of earth has been discovered as yet. The black hole of Cygnus X-1 in the constellation of Cygnus is found to be sending X-rays through the galaxy. One of the scientists who discovers the rays becomes obsessed with the possibilities of a black hole emitting anything at all, and endeavours to travel to the black hole and investigate. When he gets within distance of the black hole, he is sucked inside, and compressed by the gravity of the vaccuum.

Back on earth, the technological advancement of certain countries has lead to a space-race, spurring international warfare. As the death-toll rises, the world’s artists and visionaries attempt to destroy all advanced technology, fleeing into outerspace in hopes of finding their own private Xanadu (as prophesied by Coleridge?).

Thus ends act one, as the survivors on the planet earth are left without technology, barbarous and chaotic.

Act II:

The year is 2112, and the people of earth have taken what little technology they could salvage and recreated a civilization under the totalitarian rule of the priests of Syrinx, who have built temples everywhere, and eliminated all forms of expression but those they deem acceptable to their plan. One man working in an assembly line escapes his factory and takes refuge in a cave, where he discovers a guitar. Unaware of what it is, he teaches himself to play it, and discovering the power of emotion through music, he realizes that the people of earth (and the solar federation) are missing emotion from their lives. So, he presents his guitar to the Priests, thinking that they will welcome the uniting force of music, but they unexpectedly destroy it, and send him on his way.

He returns to the cave, and in a dream meets an oracle, who shows him a vision of the past, in which an elder race lived happily after travelling to Xanadu, where they’ve continued to explore open-minded behaviours for generations. The oracle says that one day, they will return to destroy the temples of Syrinx. On awaking, the man is so depressed by the state of affairs, believing his dream to be an illusion, that he kills himself. However, as civil wars break out in the solar federation, the elder race returns from Xanadu, alerted by the sound of the guitar, and assumes control of the Solar federation.

The act ends with the outbreak of a war between the passionate elder race, or the Dionysians, and the logical, emotionless people of the Solar Federation, or the Apollineans.

Act III:

As the Apollineans and Dionysians fight, the spirit of the scientist from Act I is sent through the blackhole and through time, back to earth where the people are warring. Seeing the chaos, he cries out for them to stop, and they suddenly realize that they require balance to co-exist. They christen the spirit Cygnus, god of balance, and he teaches them that a balance of heart and mind will mold a new society that is closer to the heart…

The End.

Yep. It’d kick ass.

You get a full cast recording of “Closer to the Heart” as a finale.

Tell me that wouldn’t kick ass.

Yeah, it’d kick ass.

Now, who wants to help me ask the members of Rush to produce?